I read with interest Dr. Larry Chapp’s recent article, “Apologetics and Evangelization Part One: Vatican II and Why Radical Traditionalism is a Dead End”. I hope to comment more on this article and its follow-up, but I’ll start with something that really stood out to me. Dr. Chapp expresses throughout that he has little patience (well, none really) for the traditionalist claim that the texts of Vatican II contain serious and harmful ambiguities. But religious liberty, the conciliar example which he cites most often to push back against the claim, seems to me a particularly unfortunate choice. In spelling out why, I hope Dr. Chapp receives this feedback in the fraternal spirit in which it is intended.

For starters, Dr. Chapp deploys a real strawman when he characterizes the traditionalist position with respect to religious liberty thus: “State coercion in confessional States to get people into the Church so that they too may be saved is seen as the best path forward”. I don’t know of any traditionalist author who holds that it is permitted, let alone desirable, for the State to coerce conversion to Catholicism. I don’t know any who would not agree with Pope Pius XII’s injunction:

We recognize that [converting to the Faith] must be done of their own free will; for no one believes unless he wills to believe. Hence they are most certainly not genuine Christians who against their belief are forced to go into a church, to approach the altar and to receive the Sacraments; for the “faith without which it is impossible to please God” is an entirely free “submission of intellect and will.” Therefore, whenever it happens, despite the constant teaching of this Apostolic See, that anyone is compelled to embrace the Catholic faith against his will, Our sense of duty demands that We condemn the act.

(Mystici Corporis Christi §104, my emphasis)

The question over Dignitatis Humanae (DH) is not whether the State has the authority to use coercion to “get people into the Church”. All parties agree that it does not and Dr. Chapp’s statement is an unfortunate caricature of his opponents’ views.

Going back to the matter of ambiguity, Dr. Chapp’s use of DH as his prime example in denying conciliar ambiguity is problematic on several levels [1]. I’ll focus here on just one.

The one great ambiguity that unarguably exists in DH is how it is to be reconciled with prior magisterial teaching. The solution is not found in the text of DH itself, as DH never interacts with prior magisterial teaching. The tension between DH and prior teaching was recognized as problematic already during the Council itself. The official relator Bishop de Smedt reported, “Some Fathers affirm that the Declaration does not sufficiently show how our doctrine is not opposed to ecclesiastical documents up till the time of the Supreme Pontiff Leo XIII. As we said in the last relation, this is a matter for future theological and historical studies to bring to light more fully” (cited in Michael Davies, Religious Liberty, 200.) This is an astounding statement, almost the ecclesiastical equivalent of Nancy Pelosi’s “We have to pass the bill so that you can find out what is in it.” At the very least this is an outright admission, from the conciliar relator of all people, that a significant ambiguity exists and is going to purposely be left in place. Let the record show.

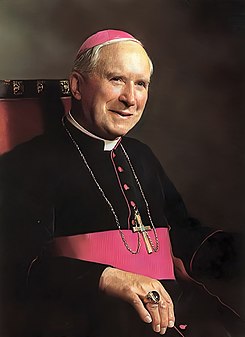

The numerous conflicting approaches which “future theological and historical studies” have advanced over the ensuing decades to answer this question further demonstrate the genuine ambiguity. In fact, a dissertation by L. J. King on “The Authoritative Weight of Non-Definitive Magisterial Teaching” focuses much of its attention on DH precisely because of these multiplying approaches to the conundrum. On p. 341 King documents three broad answers to the question – 1) that there is a genuine contradiction and the Vatican II teaching trumps the former teaching (held by theologians Francis Sullivan, John P. Boyle, J. Robert Dionne, Brian Tierney, and Albert Outler, et al.), 2) that there is a genuine contradiction and the pre-conciliar teaching trumps DH (held by Abp. Marcel Lefebvre, Jean-Michel Gleize, Brunero Gherardini, et al.) and 3) that the pre-conciliar magisterium and DH can be harmonized (held by William Most, Brian Harrison, William Marshner, Jeffrey Mirus, Thomas Storck, Thomas Pink, et al.]. Among that third group, the proposed solutions are varied and often mutually exclusive.

I’ve not read enough of his work to know Dr. Chapp’s approach to the question. But if he insists that there is no significant ambiguity in DH with respect to the prior magisterium he faces a few major hurdles. If he says that there’s no ambiguity because DH “clearly” trumps pre-conciliar teaching (solution #1) then at the very least he’s abandoned a “hermeneutic of continuity” [HOC] for a “hermeneutic of rupture” [HOR], although I’m pretty sure I’ve seen him extol the HOC before. What exactly would make it “clear” that the HOC should be applied in most cases, but that here the HOR is more in order?

If instead he were to adopt solution #3, the harmonizing approach, then for there “clearly” to be no ambiguity Dr. Chapp would need to tell us first why there are so many proposed harmonizations, if the situation is so unambiguous, and second which of the proposed solutions is definitively correct. But this can’t happen because almost 60 years after the promulgation of DH we have no official, magisterial guidance on this divisive question.

Finally, Dr. Chapp seeks to dispel the charge of ambiguity simply by asserting that no ambiguity exists. He claims there is rather a “development of doctrine” which both he and his opponent ostensibly understand in the same way, but over which they disagree: “the conciliar ‘ambiguities’…are not ambiguities at all (e.g. religious freedom) but rather are simply developments of doctrine with which he [his traditionalist opponent] is in disagreement.” But I respectfully submit that unless and until we know definitively how DH stands with regard to prior magisterial teaching – whether 1, 2, or 3 and, if 3, then which method of harmonization – we cannot definitively nail down the nature and scope of development of doctrine present in DH.

Obviously, I believe there is a significant ambiguity in this conciliar text and that it undermines Dr. Chapp’s reliance on this text to denounce traditionalists. I also hold that this ambiguity has caused real, serious, on-the-ground harm, at the very least contributing to the rupture between Abp. Lefebvre and the Holy See. That being said, I personally think that Fr. Brian Harrison has, technically speaking, successfully harmonized DH with prior magisterial teaching (see his summary article “Dignitatis Humanae: A Non-Contradictory Doctrinal Development” and the longer book-length treatment Religious Liberty and Contraception.) This affirmation does not mean, however, that I think no problem exists. Fr. Harrison’s approach is still just one among many private attempts and it remains a scandal that almost six decades after the Council we are apparently no closer to getting an official, magisterial answer to the question. It is a detailed and highly nuanced answer, which tends to beg the question how “clear” DH actually is. It is scandalous, too, that the existence of this harmful ambiguity was acknowledged even during the council sessions, but nothing was done then to address it. Such important harmonizations with prior magisterial teaching should absolutely not be left for “future theological and historical studies to bring to light more fully”. At the very least let the lesson be learned. We have seen far too much mischief worked and far too much damage done by those riffing off these ambiguities to continue that sort of behavior. (In the end I agree with Rudolph Veshtaj that whatever it is that DH teaches, it does not teach it well – see his article “The Incoherent Council: Vatican II and Religious Liberty“.)

This and other examples leave me agreeing with traditionalist commentators that there are significant and harmful ambiguities in a number of Vatican II texts. I hope and pray that these will all eventually be resolved, perhaps through a combination of official, authoritative harmonizations with prior magisterial teaching, along with official condemnations of the most prominent and harmful misinterpretations.

[1] Cf. the questions raised during a debate between Fr. Brian Harrison and Mr. Arnold Guminski: “Nearly fifty years out, the meaning of parts of this hugely important text remains controversial, and even obscure. What are the legitimate grounds for civil society’s suppression of religious activity? Are they compressed into something called “public order”? What does that term encompass? Does DH teach that the recognition of a religion as the state’s “establishment” is never just? Or is it sometimes just, but only so long as Catholicism is recognized by public authority as uniquely true?” (link). This is not an exhaustive list of the questions raised by Dignitatis Humanae.